The disparity between the rate of police traffic stops of Black and Hispanic drivers and their white counterparts shrank for a second consecutive year, according to the Connecticut Racial Profiling Prohibition Project (CTRP3).

We depend on your support. Donate to Connecticut Public today.

Though the gap is shrinking, the fifth annual report, which analyzed 2018 traffic stop data from law enforcement agencies statewide, found that Hispanic drivers are the most likely to be pulled over by state police during the daytime.

“When we look at Hispanic drivers stopped during daylight and then at the same exact time when the sun wasn’t out, we say, OK, there’s Hispanic drivers stopped when the sun was out -- why? There shouldn’t be,” said Ken Barone, project manager for CTRP3, which collects and analyzes traffic stop data from 94 municipal police departments and 13 special agencies, including 11 state police troops.

CTRP3 and its advisory board was established in 2012 to enforce and oversee law enforcement’s required data reporting, which became mandatory after passage of the Alvin W. Penn Racial Profiling Prohibition Act in 1999. Its first full report, which analyzed traffic stop data from October 2013 through September 2014, was released in 2015.

Jim Fazzalaro, a research and policy specialist who’s co-authored the annual reports, said when the project started, they were looking to create a screening tool that could provide “an annual snapshot of what traffic stops look like.”

“It’s not just putting out an annual report that points a finger at police agencies and then just simply stops. What follows the initial report … is a very involved process of taking those departments that have been identified and sitting down with them to talk about what they do, to talk about their approaches,” Fazzalaro said, “to show them what we see in their data and to engage in a process of both understanding what their policies are, why they do what they do and then showing them … to try to get to some understanding of why the data is the way it is.”

The 2018 Analysis

The report identified State Police Troop K -- whose jurisdiction encompasses more than a dozen towns, including Colchester, Portland, East Haddam, Lebanon -- as having a disparity in the rate of minority traffic stops according to what’s known as the Veil of Darkness test. Troop K was also identified in the 2017 annual report.

That test looks at stretches of daylight and darkness to determine whether a particular minority group is being stopped more or less frequently based on visibility, given that there are no changes in the number of minority drivers on the road during those distinguishable periods. Barone used Black drivers as an example.

“If you stop 20% of your drivers are Black when the sun is out, you should be stopping the same percentage of Black drivers when it’s dark out,” Barone said. The number, he said, should be constant. “And if there’s a difference, what that tells us is that you’re potentially, because you’re more able to see who’s in the car, discriminating against them.”

Though Troop K was the only troop formally identified, the report made note that it “warrants concern that the Connecticut State Police have appeared each year as having a statistically significant disparity in either or both of minority traffic stops and vehicular searches.”

"We are always looking for ways to improve our service and trust between the community and our state troopers,” said Brian Foley, a spokesman for the state Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection. “The bottom line is if our community and our citizens feel there’s an issue, then certainly we have to recognize that. Our many state police troops are vastly different and serve many populations throughout the state,” he said. “We look forward to continued evaluation and conversation.”

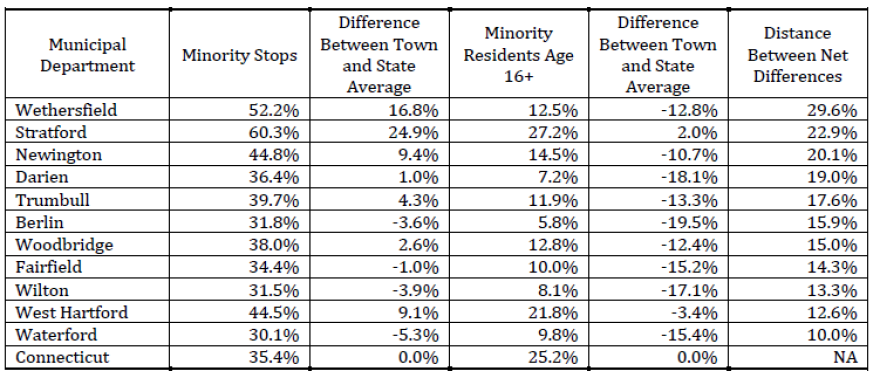

Minority Traffic Stops By Municipal Police Departments

The report also found that Darien, Manchester, Meriden, Newington, Norwich, Stratford, Waterbury and Wethersfield exceeded the disparity threshold with multiple census-based benchmarks. The three benchmarks are statewide average, the estimated commuter driving population, and resident-only stops.

Data showed that some of those same towns stop minorities at higher rates, despite having predominantly white populations.

For the study period from Jan. 1 through Dec. 31, 2018, the statewide percentage of drivers stopped by police who were identified as minority was 35.4%. The report defines minority as “all racial classifications except for white drivers … Blacks, Hispanics, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and other race classifications included in the census data.”

According to census data, Connecticut is 66.5% “white, alone,” 16.5% Latino/Hispanic, 12% “Black or African American, alone” and 4.9% “Asian, alone.”

A total of 29 departments stopped a higher percentage of minority drivers than the state average, including 15 that exceeded the statewide average by more than 10 percentage points.

Once a department’s data has been analyzed, the CTRP3 team works with departments.Fazzalaro said sometimes it’s “very clear” why disparities are likely occurring in a department’s traffic stop data and sometimes it’s “not clear.”

Disparities Within Stops, Searches

The report also pointed out that police in Waterbury and New Haven stopped and searched more Black and Hispanic drivers than white drivers, but the rate of contraband found with white motorists was significantly higher. The New Haven Police Department found contraband in 51.7% of searches (31 of 60 searches) for non-Hispanic Caucasian motorists but only 20.9% (87 of 416 searches) for Black motorists and 42.1% (64 of 152 searches) for Hispanic motorists.

The Waterbury Police Department found contraband in 48.5% of searches (50 of 103 searches) for non-Hispanic Caucasian motorists but only 20% (23 of 115 searches) for Black motorists and 26.6% (21 of 79 searches) for Hispanic motorists.

According to the report, some Connecticut residents had expressed concern about the stops made for violations that are perceived as more discretionary in nature or “pretext” stops that could make the driver “more susceptible to possible police bias.” Those types of stops could include defective lights, excessive window tint, or a display of plate violation -- each of which, “though a possible violation of state law, leaves the police officer with considerable discretion with respect to actually making the stop.”

A statewide combined average for stopping drivers for pretext stops is 13.6%. Of the 94 municipal police departments, 60 police departments exceeded the statewide average. The departments with the highest percentage of stops conducted for these violations were Winsted (42.4%), State Capitol Police (42.2%), West Haven (33.6%), Middletown (30.5%) and Plainfield (29.1%).

Next Steps

In past years, anywhere from three to 10 municipal police departments and multiple state police troops were formally identified as having statistically significant racial or ethnic disparities. This year only one municipal department and one state police troop were identified for significant racial disparities based on their traffic stop data.

“The Connecticut Police Chiefs Associations as well as its member departments are committed to fair and impartial policing,” said Chief L.J. Fusaro, Groton’s police chief and a member of CTRP3’s advisory board. “The latest report makes it clear that there is benefit gained when Connecticut agencies work together to make improvements in public safety matters that are important to Connecticut citizens.”

By July 2020, CTRP3 will begin working on a comprehensive report that will analyze six years of traffic stop data from the Wethersfield Police Department. The 2018 report marks the first year the department wasn’t identified for disparities using the Veil of Darkness test, which Barone describes as the “gold standard” of statistically sound methods used to identify potential discriminatory policing patterns.

While the Bridgeport Police Department was identified as having significant racial disparities using the Veil of Darkness test, data for the first half of 2018 in Bridgeport was incomplete and couldn’t be properly analyzed, according to Barone. CTRP3 plans to produce a separate report using data from July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2019.

“We are significantly more informed about the factors that drive the disparities in policing … data is a powerful tool … We’ve been at this now consistently for eight years.” Barone said. “When you consistently stay focused on an issue and you try and chip away at the problem bit by bit, eventually what you will see is progress is being made.”